Scotsman Obituaries: John Byrne, artist and writer whose characters were rooted in comedy of real life

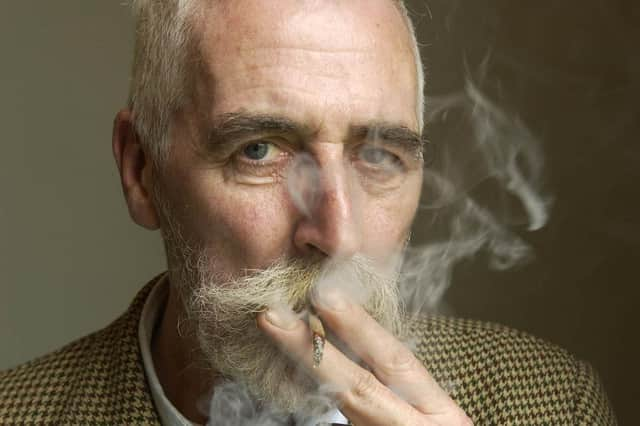

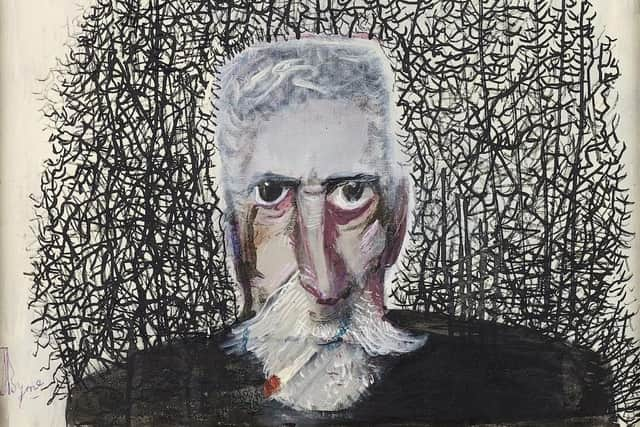

John Byrne artist, playwright and designer, was truly protean. Proteus, the Greek god who gave us the adjective, was an elusive shapeshifter and there is something about that with John Byrne too. He was first and foremost an artist and his self-portraits were a constant. In his retrospective last year, John Byrne: a Big Adventure, there were more than 40. In them he is dizzyingly protean in the styles he deploys for his self-image, but he is more chameleon than magpie. A virtuoso, he can paint himself as almost invisible in a cloud of smoke using the divided colour of the neo-impressionists, or still perfectly recognisable in the disjointed forms of cubism.

These self-self-portraits are not vain, however, nor are they really introspective. They are more enigmatic; he is in disguise, or partly visible, wreathed in cigarette smoke. In The Studio, his presence is only implicit in objects scattered round an empty room, but perhaps also in a single eye on a torn up painting. His self-portraits are, however, also a direct link to the dramas he wrote, for the latter frequently drew directly on his life. His first major success, The Slab Boys, was semi-autobiographical. Written in Paisley Scots, it premiered in 1978, but was set in 1957, the year he had himself worked as a slab-boy, a colour mixer in what he called a “Technicolor hell-hole” at AF Stoddard & Co’s carpet factory near Paisley. The Teddy Boys of late 1950s Paisley with their drainpipe trousers, extravagant hair and love of rock'n'roll, were also a constant motif in his later art.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdByrne was born in Paisley in 1940. He left school in 1957 without taking Highers and went to work at Stoddard’s. He then enrolled at Glasgow School of Art, transferred briefly to Edinburgh College of Art, and, returning to Glasgow, took his diploma in 1963. He was a wonderful draughtsman and won the Art School’s Newbery Medal. He was also awarded a travelling scholarship which took him to Italy between 1963 and 1964. He then worked as a graphic designer for STV before returning to Stoddard’s as a carpet designer. The early Sixties was not an easy time for artists and after reading about the success of “primitive” Sunday painters, in a piece of rather outrageous shapeshifting, Byrne approached the Portland Gallery in London with work much in the style of the Douanier Rousseau. He claimed it was by his father, Patrick Byrne, introduced, with a letter about his hard life and the lonely solace of his paintings, as a “primitive artist” who signed himself Patrick. Although he confessed to the deception, Byrne had several successful shows with the Portland Gallery. A commission for a record cover for the Beatles followed. The record became the White Album with nothing on the cover, but Byrne’s design was used later for the Beatles Ballads. In 1967 he wrote to Belgian surrealist René Magritte and was greatly encouraged by Magritte’s thoughtful reply. Linking his own art to the “great” art world beyond Scotland, it was a valued endorsement.

After the success of Patrick, Byrne left Stoddard’s for the theatre. In 1972 he designed the sets and costumes for The Great Northern Welly Boot Show, written by Billy Connolly and Tom Buchan, and in 1973 did the same for The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black Black Oil. In 1974 he painted a gable-end mural in Glasgow, Boy on Dogback (now destroyed) in the style of Patrick. The following year, however, after an exhibition at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow, he withdrew from exhibiting, not showing again until 1991.

Meanwhile, in 1976 he began his career as a dramatist with the radio play Writer’s Cramp, made into a stage play the following year. In 1978, The Slab Boys was launched with great success at the Traverse in Edinburgh. It transferred to London and was followed at the Traverse by two further parts, making a trilogy, Cuttin’ a Rug (1979) and Still Life (1982). A fourth part, Nova Scotia, was added in 2008. In 1983 the Slab Boys was performed at the Playhouse Theatre New York and in 1996 he directed a film version.

Byrne’s first real popular success came in 1987 with TV drama Tutti Frutti. It won six BAFTAs and launched the careers of Robbie Coltraine and Emma Thompson. Byrne painted striking portraits of the actors in character, both for this series and for Your Cheatin’ Heart, also made for TV, which followed in 1990.

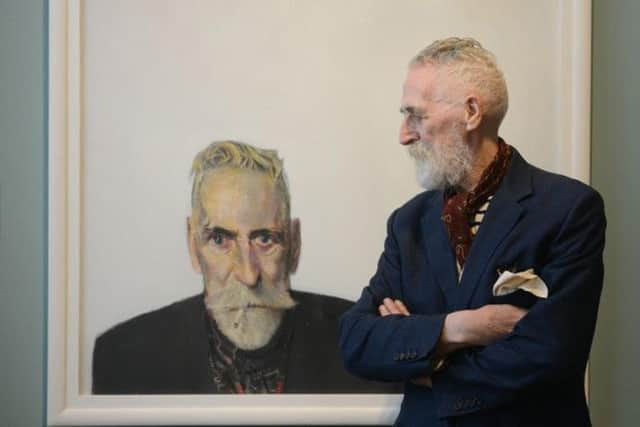

In 1991, Byrne returned to exhibiting and did so prolifically thereafter. Working at Glasgow Print Studio, prints also became a major part of his production. In 2014, Sitting Ducks, an exhibition of his portraits at the SNPG, also demonstrated what a vivid and original portrait painter he was. His portrait of Steven Campbell is particularly memorable and in 2017 his portrait of Billy Connolly was turned into a mural in Glasgow.

Fittingly, bringing together the two principal sides of his diverse talent, art and theatre, in 2013, Byrne was commissioned to paint the domed ceiling of the King’s Theatre, Edinburgh. He painted it with the sun, the moon, and theatrical figures circling a notional stage. Written on a long, fluttering banner are Shakespeare’s words, “All the world’s a stage”. It is a brilliant, visual epitome of theatre. In the same way, the strength of Byrne’s writing was his visualisation of his characters and their settings, while drawing on the imagery of his own life as he so often did gave his work a unique comic authenticity. Already reflecting this, in 1978 the critic of the Times wrote of the Slab Boys: “Mr Byrne's people have the complexities of real life in their cartoon clarity.” All Byrne’s characters, dramatic or visual, were rooted in the comedy of real life in just that way. In his later self-portraits Byrne was merciless in depicting the advance of age and illness and for all his shapeshifting, it is the core of authenticity with its tap root deep in his own experience that gave his work such strength.

Byrne was awarded an MBE in 2002, but returned it because of the invasion of Iraq. He was elected RSA in 2007 and awarded honorary degrees by the universities of Stirling, Paisley, Dundee and Robert Gordon’s, Aberdeen. He married Alice Simpson in 1964. They had two children but divorced in 2014. He was also the father of twins with Tilda Swinton with whom he had a long relationship that ended in 2004. In 2014 he married Jeanine Davies.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), or have a suggestion for a subject, contact [email protected]

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.