1984 miners' strike: On 40th anniversary, I remember their pride, solidarity and patriotism – Henry McLeish

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the start of the official miners’ strike in 1984. For many Scots, there will be little cause for either reflection or remembrance.

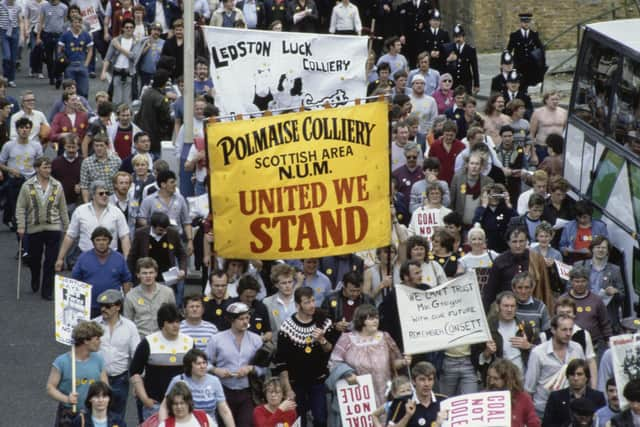

For others, the final stand of the miners will be remembered for the hate-filled struggle between Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher – determined to break the miners’ union, and the broader trade union movement, privatise the coal industry, and close pits – and the NUM leader Arthur Scargill – determined to defeat privatisation and repeat the previous victory over the Tory government when a severe shortage of coal resulted in a crisis and Ted Heath losing the 1974 general election.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ’84 strike itself was bitter, divisive, ugly, and often violent, with an outcome that seemed inevitable from the start, but no one predicted it would last for a year. My father and grandfather were coal miners, so for me it was personal. This was the miners’ last stand to defend a way of life and an industry that fired our industrial revolution, helped Britain to victory in two world wars, and overcame bondage and serfdom, a form of slavery in earlier days.

Deaths, accidents and illness

It offered the most dangerous and dirty work environments that nature has ever devised. For me, miners were special people, super-workers steeped in family and community. They were also patriots, who didn’t fight for their country on the battlefield, but were instead asked to keep digging for coal. The men descended daily in pit cages all over Britain, uncertain of whether this might be their last shift.

At its peak, Fife had 30,000 miners and 50 pits. This was a huge industry with a massive workforce. Everyone new someone who worked in the mines. This made accidents, death and illness all the harder to deal with. The often-feared knock at the door happened once when the police arrived to say my father had been severely injured in the Wellesley Colliery in Fife, where a conveyer belt had snapped. He nearly lost both legs. Luckily, he survived. Following a year in hospital, he was pensioned out of the industry after 30 years.

My grandfather worked in the same colliery, but before it was nationalised in 1947. He worked in the soup kitchens during the 1926 miners’ strike, usually wearing his best suit, collarless white shirt and, symbolically, a red rose in his lapel. He was a proud man. Never a political neutral, he was always keen to tell me about the hellish conditions in his pit, revealed by the dust that still lay between his skin and every ridge of his spine, the result of working in narrow and dangerous coal seams with roofs liable to collapse at any time.

An experience never to be forgotten was witnessing a friend of my father dying in bed of the “dust” – pneumoconiosis or black-lung disease. He was in unimaginable pain as he sucked in air from a metal oxygen tank by his bedside, hanging on to the limited life he had remaining.

Great industries became history

Sometimes it is humbling just to reflect on the sacrifice that people made for the lives of others and the country. Thatcher valued selfishness and individualism as the spirit of the free market, but on community and solidarity, she was lacking. Sadly, today, our politics seems reluctant to embrace that deeper understanding of the value of life and sacrifice which seems to be old fashioned, but which in reality is a timeless assertion of what Robert Burns described as “the dignity of man”.

The miners and their families were under no illusions about what the outcome of the strike might be: the last chapter of a once-great industry. Within a 20-year period, Scotland saw its great industries become history, with the demise of shipbuilding on the Upper Clyde, the death of the coal industry, and, with the closure of Ravenscraig, the end of the steel industry.

As leader of Fife Regional Council during the strike, we tried to compensate men and their families for the hardships being inflicted upon them by the might of the state. Families were distressed and literally breaking up in front of us, benefits were being denied, rent arrears climbed, bills went unpaid and the council even cut down trees for firewood.

Picket line violence

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFamilies were being starved into submission, but we were determined to struggle with them. Families stayed loyal to their communities, their industry and their considerable history, but not to Arthur Scargill, who many despised and were more supportive of Mick McGahey, the tough but likeable leader of the Scottish miners.

Picket line violence frequently erupted and there was no end of provocation from both sides. Tension, anger and the heat of the moment often led police and miners to the brink and beyond. Many ended up with charges and a criminal record. The courts and prosecutors responded to government pressure by taking a hard line. This only added insult to injury. For miners with no previous charges or arrests, this became a shadow hanging over their lives, grounds for dismissal, and a barrier to seeking new employment.

But as a result of spirited campaigning and the courage of the Scottish Parliament, a Bill was passed in June 2022 providing pardons for men who had no previous convictions. Wales and England have never followed suit. This came too late for some miners who sadly died with this mark against them.

There will be mixed views of ’84 but, through my personal lens, pride, loyalty, solidarity, sacrifice, heroism, work ethic and, especially, patriotism will be in full view on this anniversary. This was a sad ending for a great industry. Thatcher got her way. Scargill just faded away. The state-sanctioned dismantling of the coal industry, alongside her deeply offensive remarks implying the miners were “the enemy within”, saw Thatcher become one of the most hated figures in post-war Scottish politics. This memory hasn’t faded.

Henry McLeish is a former Labour First Minister

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.